Contact: For more information about this topic or to schedule an interview, please contact CJCJ Communications at (415) 621‑5661 x. 103 or cjcjmedia@cjcj.org.

Introduction

California’s Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ), the state’s youth correctional system, is endangering youth by subjecting them to life-threatening drug overdoses and excessive use of force by staff. Meanwhile, youth must fend for themselves amid staff shortages and a lack of programming in a highly volatile and violent environment. DJJ will close on June 30, 2023, bringing an end to its long and troubled history. However, DJJ’s long-standing dysfunction coupled with poorly developed transitional plans are undermining this transition and placing youth at great risk.

On September 30, 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law Senate Bill (SB) 823 requiring California’s state youth prisons to close by June 2023 (State of CA, 2020). SB 823 ushers in a new era of localized juvenile justice that is founded on community-based services and incarceration alternatives. These alternatives allow youth to complete juvenile court sentences in their community instead of in state-run correctional facilities. They include intensive family interventions, case management with support services, reentry housing and employment services, and graduated transition from high security to low security facilities.

Youth at DJJ and their families are facing an uncertain future. Community-based organizations serving our state’s most vulnerable youth, many of which operate at the county level, offer crucial guidance and financial resources to those impacted by DJJ. Yet the state is failing to fully collaborate with these organizations as part of the upcoming transition to a county-based system.

By closing DJJ, California can adopt a behavioral health approach that focuses on community and family support. However, this realignment to local control raises many concerns. Can California leaders and county probation departments adopt a new and broader vision? Regrettably, many counties are replicating DJJ’s harmful practices at the local level, with an emphasis on locking youth in detention centers. Youth justice organizations have worked tirelessly to improve this process. These groups prepare support services for youth transitioning from DJJ to their home counties. They also advocate for humane alternatives to confinement. Unfortunately, DJJ lacks a clear transition plan and refuses to work with entities outside of the county probation system. This failure will leave hundreds of youth without needed support when DJJ closes.

Until then, DJJ remains a hazardous place where the threat of violence and callous treatment is ever present. The approaching closure and a dwindling youth population are fostering complacency. State officials are focusing less attention on operations and show little concern for youth safety. Only continued vigorous independent oversight offers partial protection as conditions deteriorate. This has never been more critical.

Key Findings

The following key findings raise serious concerns about youths’ safety:

- Drug overdoses occur regularly inside DJJ’s high security institutions. The pervasive availability of illegal drugs puts youths’ lives at risk. Despite the danger, there appears to be a conscious and coordinated effort by DJJ to withhold information about the crisis from the public and state officials.

- Ventura Youth Correctional Facility reports more than double the suicide interventions a month compared to the other open facilities.

- Staff at the Ventura Youth Correctional Facility routinely employ chemical spray against youth at rates higher than any other DJJ facility.

- Staff shortages have grown significantly over the past three years. Nearly four in ten positions are now unfilled, further increasing youths’ risk of violence and isolation.

- Youth in the general population spend less than 10 hours a day outside of their cells. Staff keep youth in DJJ’s disciplinary units (BTP) even more isolated, leaving them in cells for more than 20 hours a day.

This report highlights DJJ’s crisis before closure. We document current grievous conditions, alarming organizational decline, and defeatism among its administration. This creates concerning patterns around contraband, staff misconduct, injuries, mental health, programming, and reentry planning and communication. California leaders must immediately address DJJ’s dangerous conditions by holding administrators and staff accountable and sending the remaining youth home.

Division of Juvenile Justice Overview

The Division of Juvenile Justice, formerly known as the California Youth Authority, or CYA, has a long history of being a violent and dangerous place for youth. While the name may have changed, conditions inside these facilities remain bleak. These state-run youth prisons, which are intended to confine youth who have committed serious crimes, are notorious for subjecting youth to violence.1

DJJ has its origins in the 19th century reform school movement, which was founded on the idea that youths’ misbehavior could be addressed by placing them in adult-style penitentiaries (Macallair, 2015). After over 100 years of withering controversy, Governor Newsom made the decision in 2020 to bring this cruel system to a close. Throughout DJJ’s history, its institutions were the site of brutal violence and cruelty and widely denounced as schools of crime.

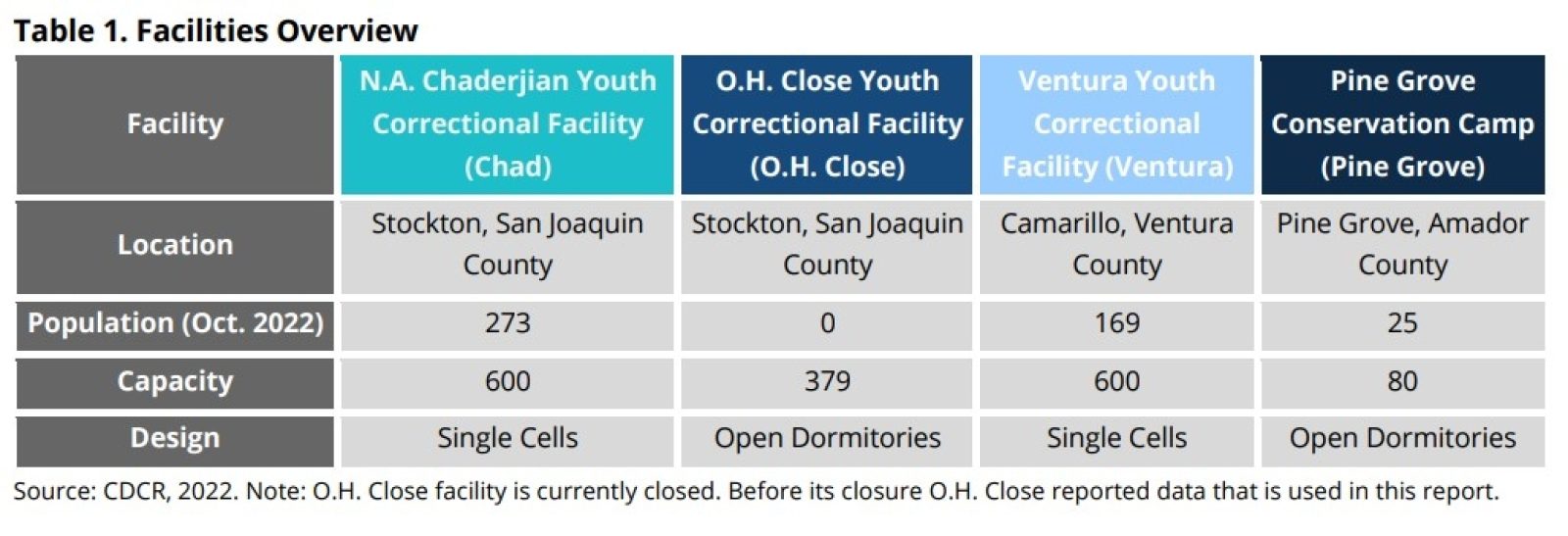

Currently, only three of these facilities are left: N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility (Chad) a facility that confines male youth; Pine Grove Youth Conservation Camp (Pine Grove) a conservation camp for male youth; and Ventura Youth Correctional Facility (Ventura) a facility that confines both male and female youth. The population of these facilities is rapidly declining due to SB 823, which halted juvenile court commitments to DJJ after July 1, 2021 (SB 823, 2020).

Alarming Drug Overdoses

In September 2022, we learned of alarming drug overdoses inside DJJ facilities. According to witnesses, these overdoses were occurring in all units of the largest facility, Chad (Interviews, 2022). DJJ administration has ignored repeated attempts to obtain information about these incidents. Sources report a variety of different drugs are causing these overdoses, one of the most disturbing being fentanyl, a dangerous drug responsible for an increase of overdose deaths in California (CDPH, 2022; Interview 2022). DJJ administration has not provided information about the capacity of the system’s health services to handle such potentially severe health emergencies, and it has failed to disclose whether youth have access to outside medical care following an overdose. Addressing an opioid crisis requires specialized staff training and an immediate medical response, including the distribution of Naloxone.

We do not know if all facilities and staff have access to Naloxone, also known as NARCAN, a medication that reduces the symptoms of opioids. Overdoses are now occurring in county juvenile detention centers across the state, forcing county officials to fashion new emergency responses. Recently the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, concerned that the county probation department was unprepared for this crisis in its facilities, passed an ordinance mandating that all juvenile justice facilities have Naloxone available.

Contraband Continues Despite Increased Security Measures and Halt to Visitation

Drugs, weapons, and other unauthorized items appear to be easily obtained within DJJ, a longstanding issue that threatens youth safety. DJJ’s security measures fail to prevent the availability of contraband, which enters through staff or visitors. DJJ has strict security measures for preventing visitors from introducing contraband into its facilities. Staff use pre-screening measures, metal detectors, and belongings searches on visitors prior to entry. Newly added COVID precautions have simultaneously strengthened anti-contraband efforts. Visitors must now stay six feet apart from youth, with no physical contact between them (CDCR, 2023). This virtually eliminates opportunities for transferring contraband but erodes important family relationships.

The regulations for staff are far less stringent. While visitors are pre-screened and then searched before entering a facility, staff are not searched when they arrive for their shifts. In the event that staff are searched, they usually receive notice beforehand (Interviews, 2022). This advance notice allows staff members to choose what items they bring inside a facility on the day of their predetermined search. Staff members who bring contraband inside the facility can use these announced searches to their advantage.

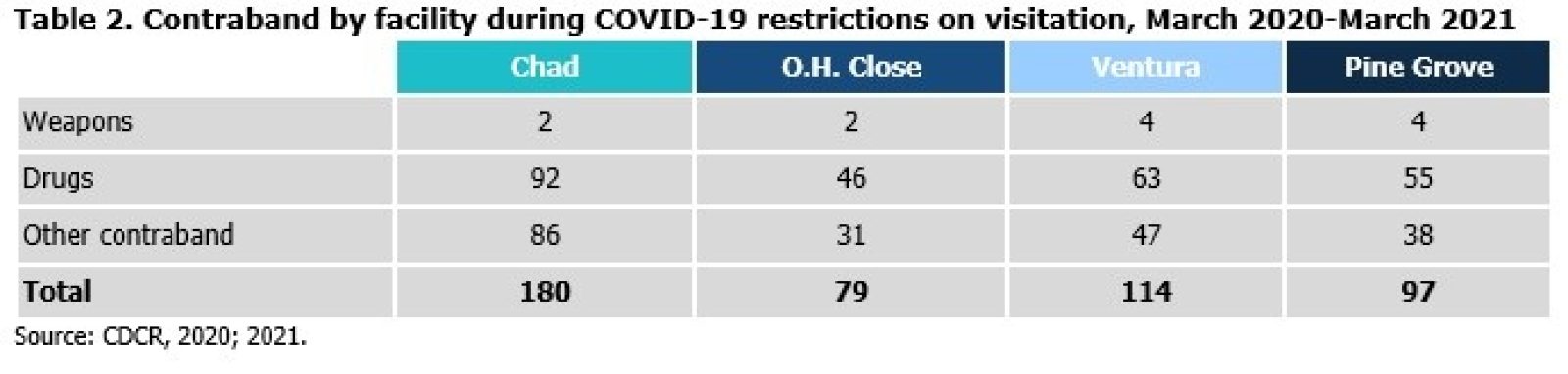

We believe DJJ staff are likely the primary source of illicit material, including dangerous drugs. Contraband is still prevalent at DJJ despite the differing standards for visitors and staff. This was made clear after DJJ halted in-person visitation with the onset of COVID-19.2 During this time, DJJ staff continued finding contraband despite no visitors entering the facilities (CJCJ, 2023).

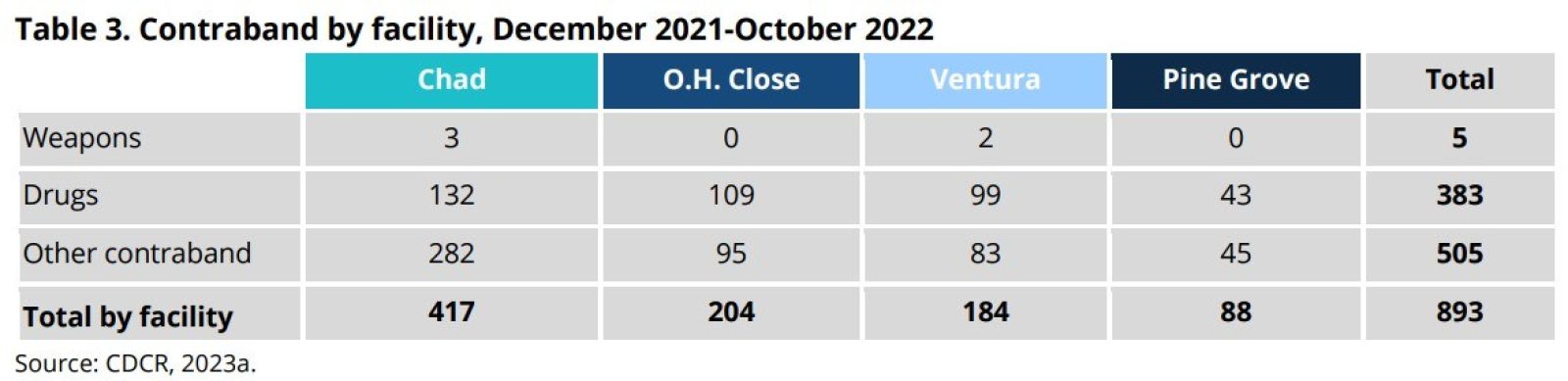

New data shows similar trends, as drug contraband is readily available in DJJ. In less than a year (December 2021 — October 2022), DJJ reported almost 400 incidents of drug contraband. During this same period, DJJ housed an average of only 562 youth, which suggests that drugs are widely available and a daily threat to youths’ well-being (Table 3).

DJJ Staff, But Not Youth, May Escape Punishment for Contraband

Staff and youth face different repercussions when caught with contraband. When youth are caught with contraband, the penalties can be serious. It can compromise their future hearings for less restrictive programming (step-downs), add time to their sentence, reduce or eliminate their program time, or even result in adult court charges. Though staff can be fired or charged with a crime when they are caught having brought contraband into DJJ, such penalties are rare. This 2021 incident illustrates this point:

“Between January 13, 2021, and May 4, 2021, a senior youth counselor, two youth counselors, and a teacher allegedly conspired with wards and introduced marijuana, vape pens, and mobile phones into a facility. The Office of Internal Affairs conducted an investigation, which failed to establish sufficient evidence for a probable cause referral to a district attorney…The Office of Internal Affairs’ performance in analyzing allegations from the hiring authority was poor because, in the OIG’s opinion, the Office of Internal Affairs should have added applicable misdemeanor allegations and opened a concurrent administrative case.”

Pervasive Mental Health Issues and Suicide Incidents

The prevalence of suicide related incidents is another way to understand the DJJ environment. Currently, the Ventura and Chad facilities have the highest numbers of suicide related incidents. These incidents are recorded by staff as suicide intervention, suicide precaution, suicide watch, attempted suicide (self-harm & behavioral), and suicides.3 Fortunately, no facility has reported a suicide between December 2021-October 2022. However, some facilities have higher rates of suicide intervention and suicide precaution. Ventura has a much higher monthly average for suicide intervention (12 incidents) and suicide precaution (9 incidents) compared to the average of the other facilities combined; which had a monthly average of five incidents of suicide intervention and seven incidents of suicide precaution.4If we account for population, Ventura’s numbers are still high. Each month at Ventura, the equivalent of 6% of youth require a suicide intervention and 4.6% are on suicide precaution.

However, we cannot draw a definitive conclusion regarding Ventura’s high suicide incident numbers. Perhaps these figures reflect greater responsiveness by Ventura staff or failure by staff in other facilities to properly address a potential crisis. Conversely, harsher conditions at Ventura could explain the facility’s high suicide incident numbers. Across DJJ, suicide incident rates show that youth are struggling with mental health issues that are likely exacerbated by harsh institutional conditions.

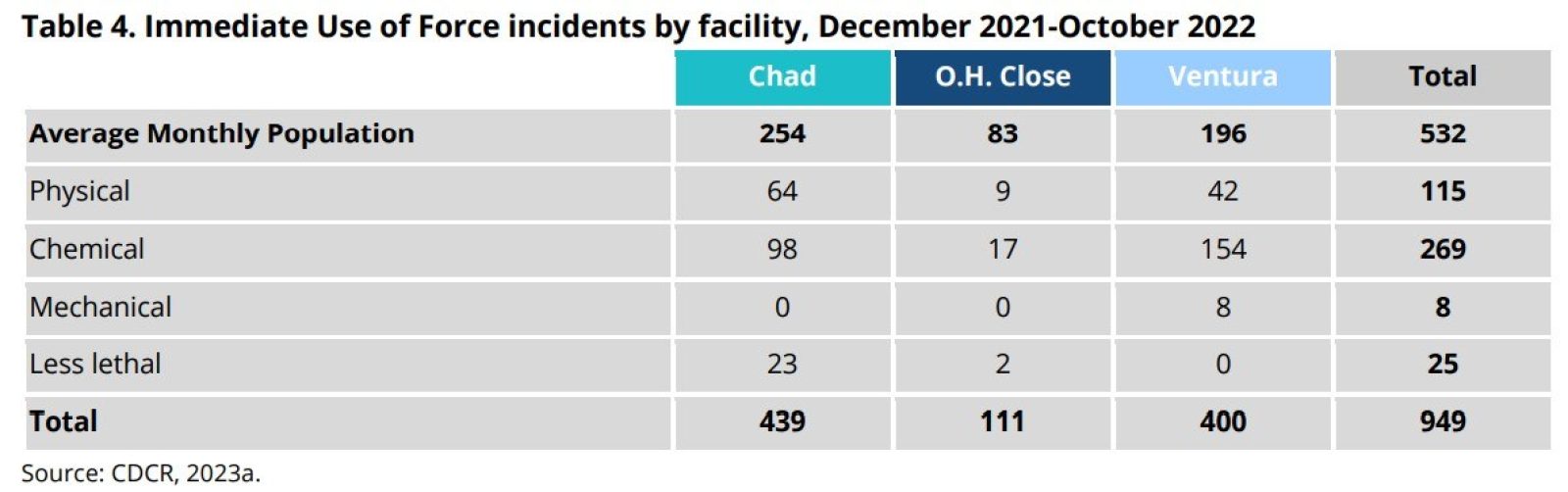

Disturbing Accounts of Injuries and Staff Use of Chemical Spray Against Youth

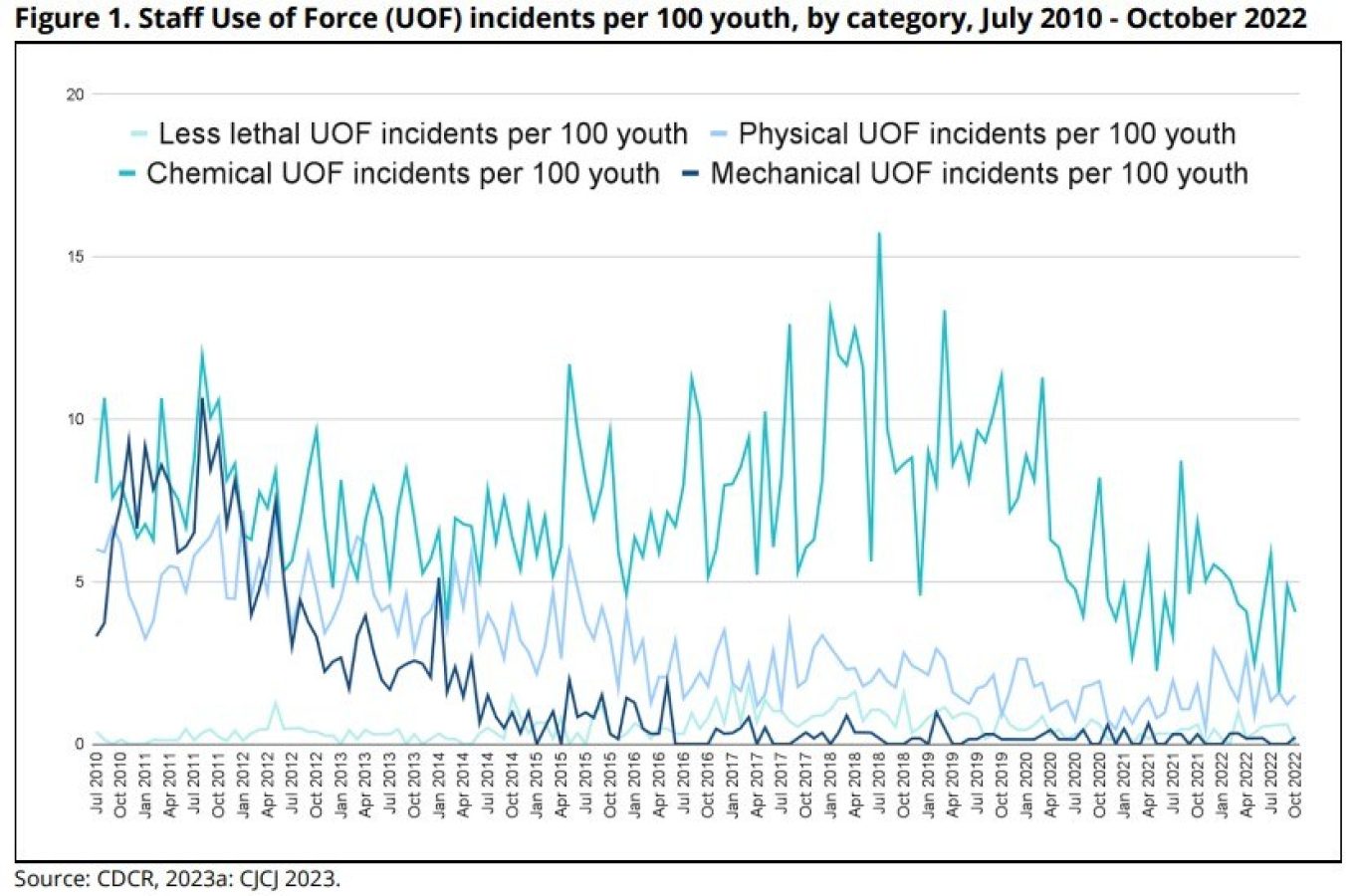

Youth at DJJ regularly experience injuries and staff often administer force against them. DJJ’s staff record immediate use of force, which measures how often staff resort to the harshest methods to address youth behavior such as physically restraining youth (physical), using pepper spray (chemical), shackling (mechanical force), or shooting rubber bullets (less lethal).5Youth in mental health units account for a concerningly high number of use of force incidents. In the Ventura facility from December 2021-October 2022, youth in mental health units made up about 16% of the population but accounted for 33% of physical and 13% of chemical use of force incidents. During the same time in Chad, youth in mental health units accounted for 5.5% of the population but 12% of physical and 10% of chemical use of force incidents. Overall, the Chad facility stands apart with the highest incidents of use of force through physical and less lethal means. While Ventura, with the second largest population, has the highest rate of pepper spray use against youth.

“That is the alternative that they use. They automatically just tell you ‘get down’ and then the first thing they do is just pepper spray you. My first time getting pepper sprayed they didn’t even tell me to get down or nothing they just sprayed me.”

Staff Use Chemical Spray Against Youth

DJJ staff depend heavily on pepper spraying youth, particularly at DJJ’s Ventura facility. From December 2021- October 2022, Ventura had 154 incidents of staff resorting to chemical spray against youth, far exceeding the numbers reported by staff at Chad (98) and O.H. Close (17). Ventura facility staff use chemical spray on the equivalent of about 7% of the population each month (about 14 youth a month) (CDCR, 2023a).

Reliance on chemical spray is widely condemned by human rights groups as an inhumane method of forcing youth compliance or maintaining order in a youth correctional facility. Chemical spray includes oleoresin capsicum (OC) spray and is commonly known as pepper spray. Capsaicin is the spray’s main ingredient, which irritates the skin, eyes, and mucus membranes of the nose, mouth, throat, and lungs. Youth experience redness, irritation, pain, watery eyes, and light sensitivity. Youth may also suffer severe injuries such as eye abrasion, skin blisters, and breathing impairments. Those with lung conditions, such as asthma, are more likely to suffer severe breathing problems after inhaling pepper spray (Dominguez, 2023). In addition to the physical effects, chemical spray can have profound psychological effects, leaving youth traumatized, resentful, afraid, and distrustful of facility staff (ACLU, 2019).

Staff use chemical spray on youth in DJJ more than any other immediate use of force method, an increasing trend since 2010. Incidents from July 2010-October 2022 show staff are overly reliant on chemical spray to a greater degree than in the past. In 2015, staff’s use of chemical spray spiked, surpassing all other use of force methods. While DJJ staff reduced other practices, such as shackling and rubber bullets, they increasingly pepper sprayed youth. DJJ’s dangerous trend shows that staff can become dependent on chemical spray when it is readily available to them. Counties may replicate this trend if chemical spray remains an option for juvenile facilities.

California is one of the few states that still allows the use of chemical spray in juvenile detention facilities. Thirty-five other states have banned or limited its use (CAI, 2022). While seven California counties have banned chemical spray in juvenile facilities, most continue using it to deter disruptive or even minor behavior. This year, California is revising the Juvenile Titles 15 & 24 Regulations, which govern operations in county juvenile justice facilities (BSCC, 2023). The state has a unique opportunity to end this harmful practice as the state shifts towards reliance on county facilities.6

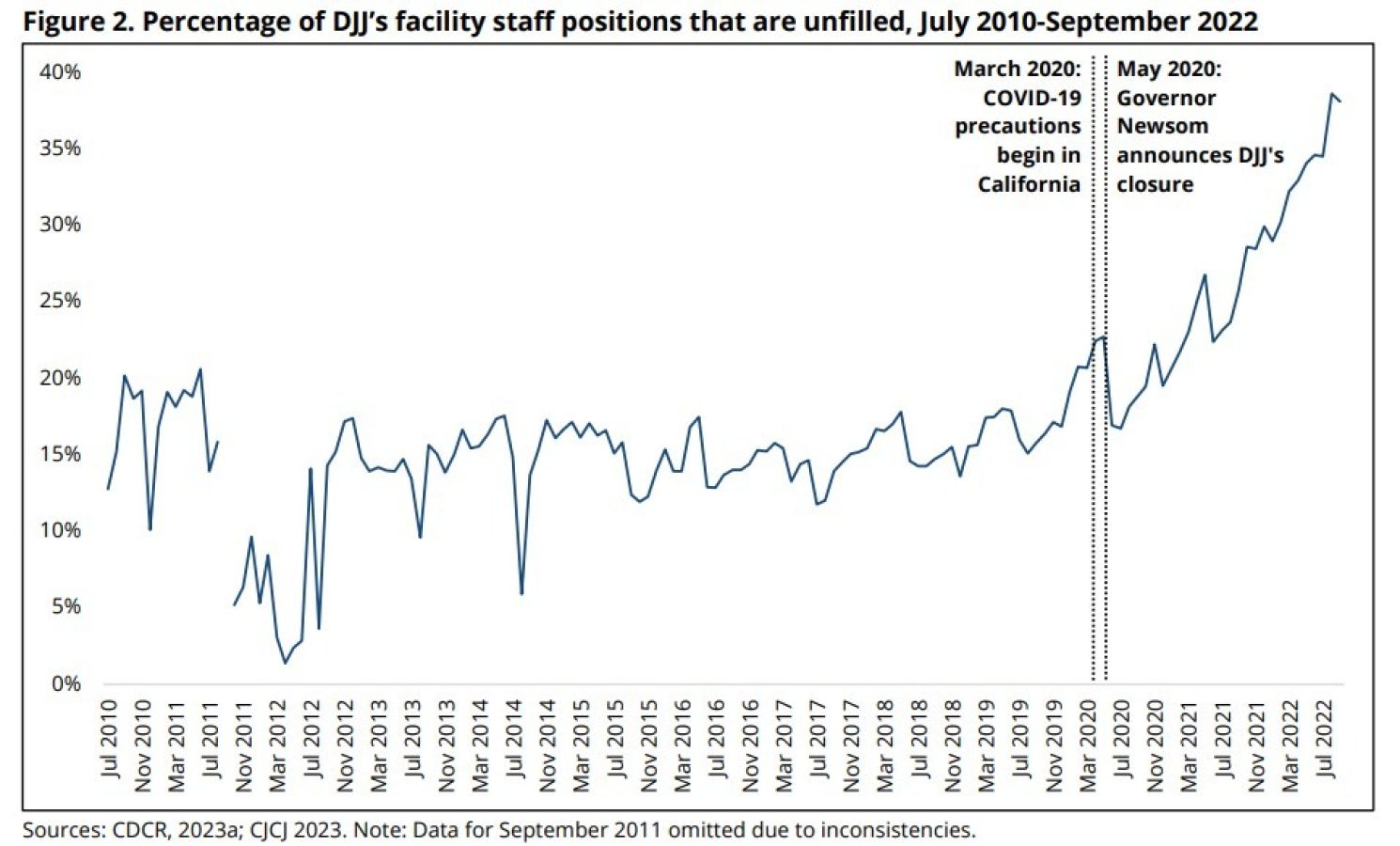

This crisis partly originated in 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic left many jails, prisons, and youth facilities short-staffed. At the time, many DJJ employees were out on sick leave for extended periods of time, while others stayed home fearing they might contract the virus. Amid these challenges, Governor Newsom announced plans to close DJJ. This decision worsened DJJ’s staffing problems as employees began seeking positions elsewhere (CJCJ, 2021).

Although California is now emerging from the pandemic, the staffing crisis continues. DJJ struggles to retain or hire qualified staff, with vacancies 31% higher than they were at the start of the year (January 2022) and 83% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic (February 2020) (CDCR, 2023a). Earlier this year, the Governor’s office attempted to slow the pace of resignations by offering DJJ employees up to $50,000 for remaining on the job until closure (Lyons, 2022). These bonuses, which are costing the state more than $50 million, have failed to stem the staff exodus (DOF, 2022). With more than one in three positions currently unfilled, DJJ cannot provide enough treatment or programming for its remaining youth. Moreover, operating short-staffed places young people at greater risk of harm. With fewer staff in the facilities, there is a heightened potential for violence, and staff may be more inclined to respond to youth with force. To prevent these incidents, DJJ relies on long and frequent lockdowns where youth are confined for much of the day in their cells.

Long Periods of Time in Cells

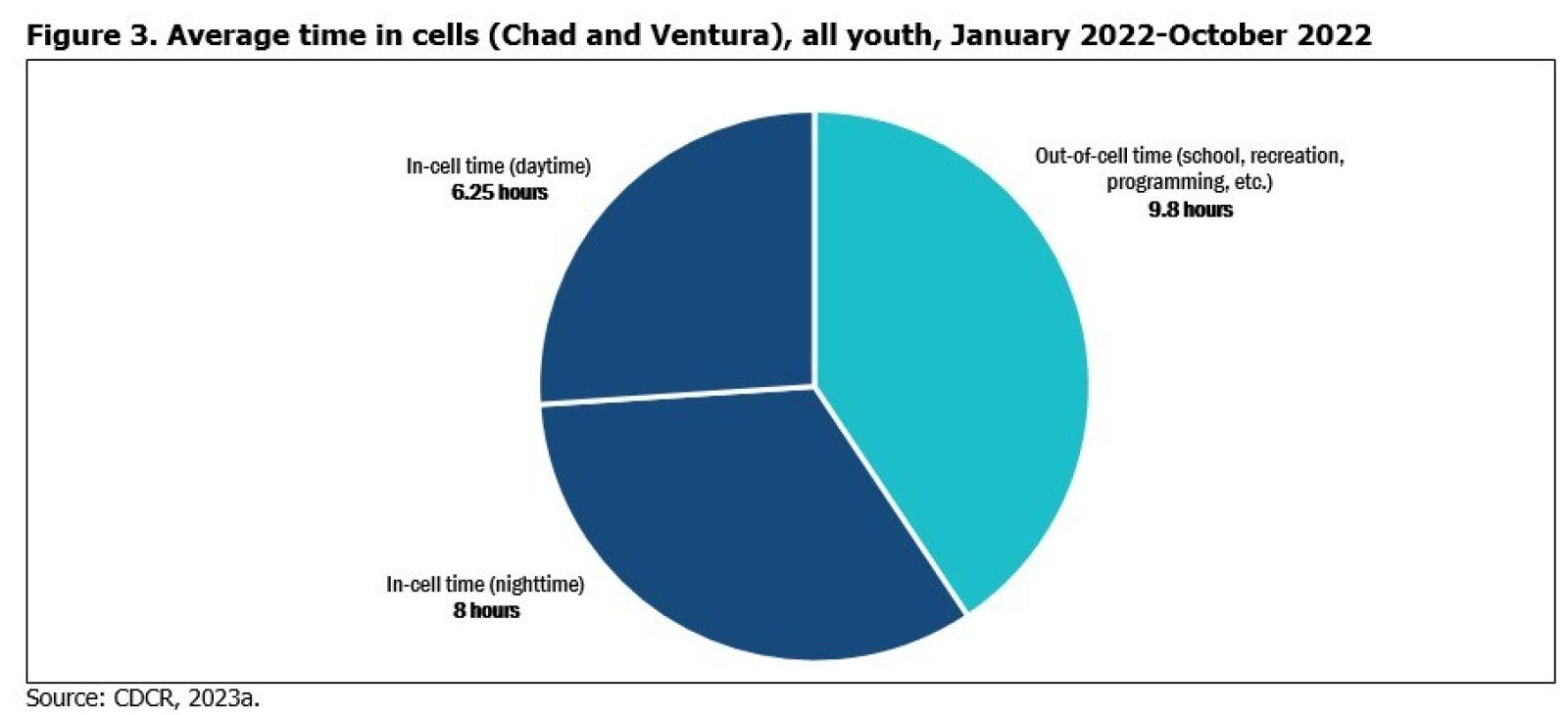

DJJ subjects youth to long periods of isolation. On average, in the two DJJ facilities with a single-cell design (Chad and Ventura), youth spent an average of just over 14 hours per day confined in their cells between January 2022 and October 2022 (CDCR, 2023a). That leaves less than 10 hours a day for school, work, recreation, and meals (Figure 3).

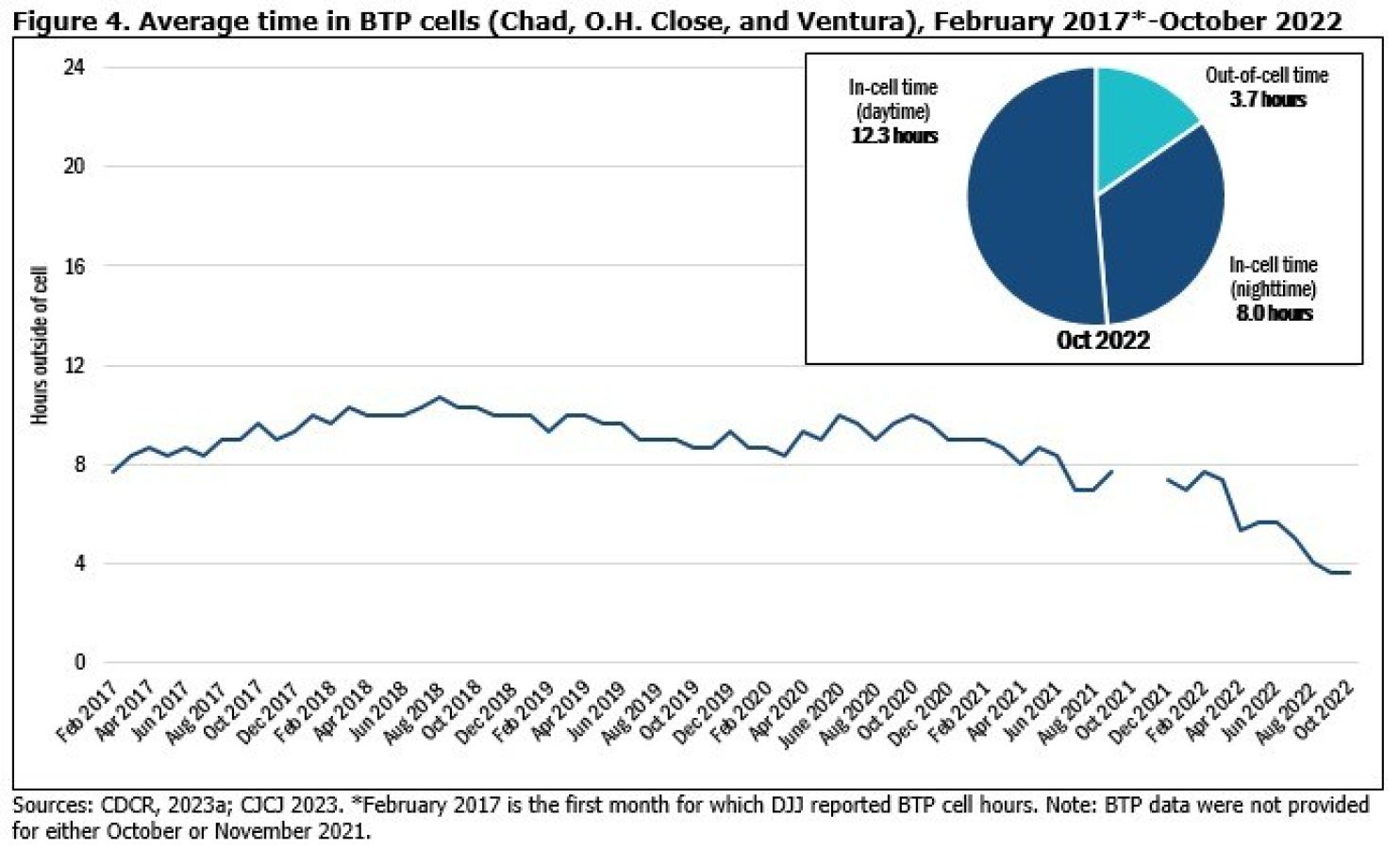

For youth in DJJ’s disciplinary units, termed the Behavior Treatment Program (BTP), the conditions are even worse. By October 2022, DJJ was allowing these youth just 3.75 hours outside of their cells per day (just half of what they received at the start of the year), meaning that, in each 24-hour period, youth were isolated for more than 20 hours (CDCR, 2023a) (Figure 4).

Cells at DJJ are sparse and cramped. When youth are locked in, they cannot get the exercise or social interaction they need for healthy development. Research has shown that isolating youth in cells is detrimental to their physical well-being and contributes to anxiety and depression (AACAP, 2017). Dependence on isolation has plagued DJJ since its founding (CJCJ, 2019; 2020; 2021; Macallair, 2015).

“[Isolation in cells] messes with you mentally, emotionally, physically. I wasn’t able to see the sun. I wasn’t able to call my mom. They restricted my freedom in every sense of the word.”

Lack of Rehabilitative Programming

Despite per capita spending of nearly $450,000, DJJ does not provide adequate programming, leaving some of California’s highest needs young people without the treatment they need to succeed upon release (DOF, 2022). DJJ’s meager programs mostly consist of a fixed number of group sessions presented by unit staff. The modules, which include topics such as anger management, substance use, and social skills, have been the backbone of programming in DJJ institutions for decades (CDCR, 2023a). After years behind bars, many youth have exhausted all programming options.

Staff shortages are exacerbating this problem. Without enough staff to hold resource group meetings, even these limited activities are being canceled or scaled down. Typically, Youth Correctional Counselors (YCCs), the DJJ staff who work with youth in their living units, are responsible for leading resource groups. However, recent data show steep declines in the shifts worked by YCCs. In October 2022, there were 67% fewer YCC shifts compared to October 2019 (just before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic). This decline has far outpaced the drop in DJJ’s youth population, which fell just 31% over this period, and even the decline in shifts worked by Youth Correctional Officers, DJJ’s security staff, which fell by 56%.

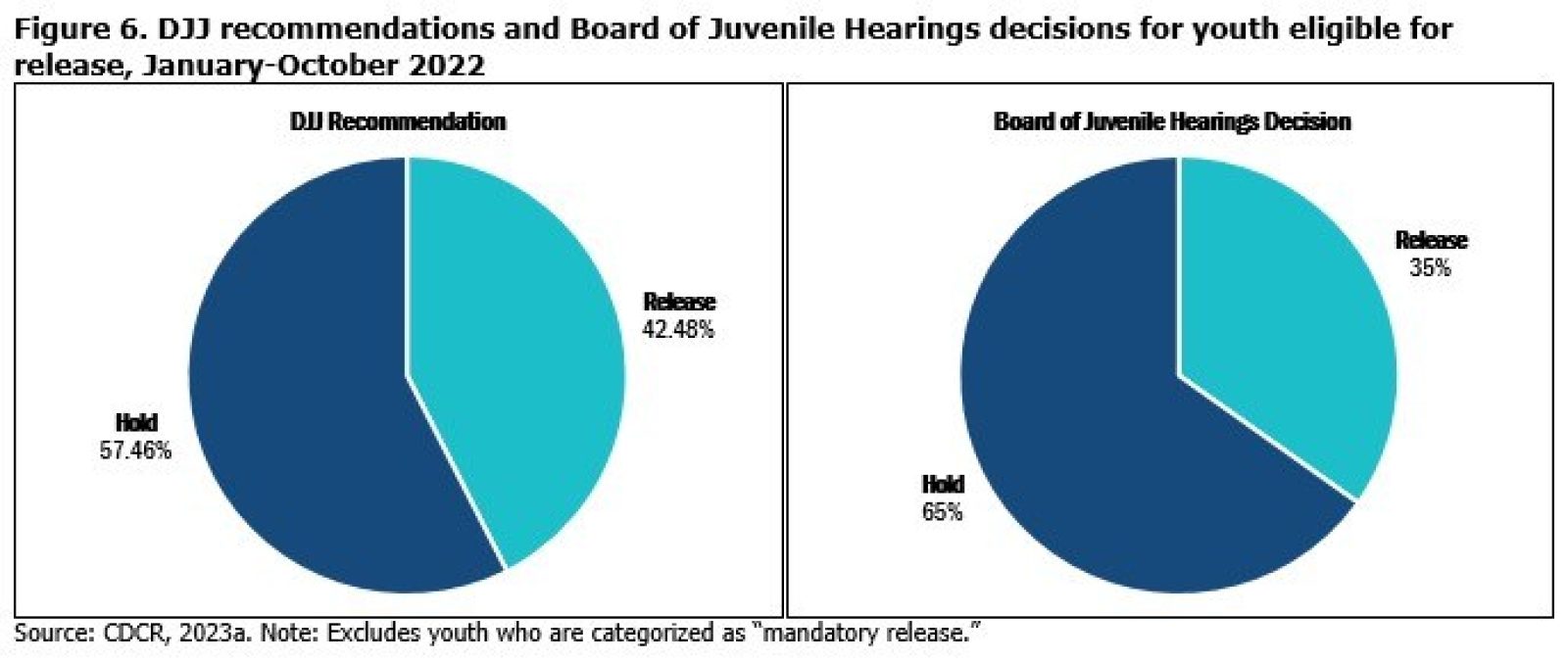

DJJ’s programming failures can negatively affect youths’ confinement time. The Board of Juvenile Hearings (the youth equivalent of a parole board) considers how many programming credits youth have accrued at DJJ when making decisions about release. If group sessions and treatment programs are canceled or not available, youth cannot complete the requirements for parole, which can extend their confinement. Youth confined during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic experienced significant programming disruptions due to frequent lockdowns and quarantines. This prevented them from demonstrating progress in their rehabilitative programs, which, in turn, affected their chances of release (Interviews, 2022).

Failing Education Programs

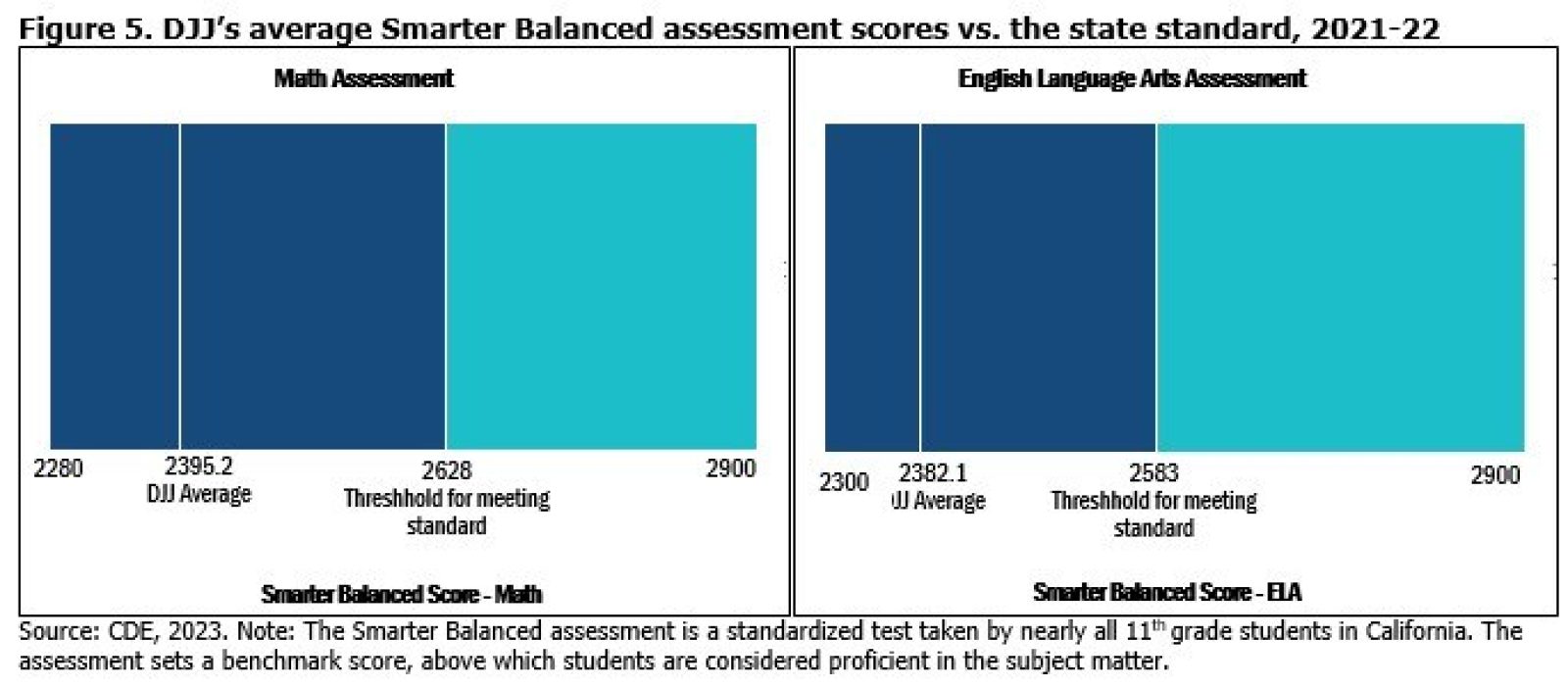

DJJ is not providing an adequate education. Youth report chaotic classrooms, absent teachers, and frequent lockdowns that disrupt the school day (Interviews, 2022). The result is poor academic performance. In the 2021 – 22 school year, no youth scored proficient in either reading or math (CDE, 2023). This suggests that none of the youth who were enrolled in DJJ’s high schools were receiving an education that prepared them for graduation. DJJ’s averages on these assessments fell well below the state proficiency standard (Figure 5).

Data from October 2022 indicate that most youth at DJJ are not enrolled in any educational program and many spend their days idle. At least 57% of youth were not enrolled in either high school, college, vocational classes, or career technical education (CDCR, 2023a; CJCJ, 2021). This figure has grown substantially over the past decade. In October 2012, just 17% of youth were not enrolled in any educational programming (CDCR, 2023a). After including youth who have a work assignment, at least 25% of youth today are unoccupied (CDCR, 2023a).7 This is significantly higher than a decade ago when just 1% of youth were not in school or working (CDCR, 2023a). For these youth, days are typically spent confined in their cells with limited opportunities for watching TV, playing cards, or socializing.

It is the fundamental responsibility of juvenile facilities to ensure that youth are receiving the education, job experience, and supportive services they need to come home prepared for success. Unfortunately, DJJ’s traumatic environment and failure to invest in youth makes it difficult for young people to find a job or continue school when they return to their communities (CJCJ, 2019).

Opaque Plans for Releasing Youth or Returning them to County Custody

With just months until DJJ closes its doors, most advocates and state leaders have turned their attention to the county juvenile justice systems that will take its place. However, for the hundreds of youth who remain at DJJ, this is a time of uncertainty. Since the closure process began in 2020, DJJ has consistently failed to communicate its plans for returning youth to their communities or to county custody. Many young people and their families are unclear about where they will be placed within the new local systems (Interviews, 2022). In late 2022, nearly three years after Governor Newsom first announced its closure, DJJ allowed a group of attorneys from the Pacific Juvenile Defender Center (PJDC) into the institutions to speak with youth about the transition, dispel myths, and answer common questions (Interviews, 2022). These sessions brought much-needed clarity and helped allay youths’ concerns.

Like PJDC, a number of private organizations have offered critical support to youth during DJJ’s transition, particularly when the state has fallen short. For example, the California Alliance for Youth and Community Justice (CAYCJ), a statewide coalition representing dozens of youth-serving organizations, has offered $500 stipends to youth returning home to a number of California counties, including Fresno, Monterey, Sacramento, Santa Clara, and San Joaquin (Interviews, 2022). These funds were an important tool in helping youth land on their feet and stay safe following their release. While the state provides several hundred dollars in “gate money” to adults leaving prison, no equivalent is available for youth (Walker, 2022). Similarly, several community-based organizations have worked closely with youth, families, and attorneys to offer reentry services to young people returning home from DJJ. Yet DJJ and county probation departments have declined to include these organizations, many with well-established reentry programs, in transition planning (Interviews, 2022).

Conclusion

California’s youth correctional institutions have a shameful, 131-year history. Now, mere months until its closure, DJJ continues to neglect youth’s basic needs and subject them to dangerous living conditions. For the hundreds of young people remaining in DJJ today, daily life is rife with violence, fear, and uncertainty. Youth are routinely exposed to dangerous drugs, extreme periods of isolation, and traumatic violence, conditions that contribute to declining mental health and suicidal behavior. Moreover, DJJ’s inadequate school, work, and program offerings, paired with poor reentry planning, are leaving youth unprepared to face the challenges of life after release.

Although DJJ’s closure will end this brutal chapter in California’s history, it will not bring an end to the harm and abuse that exists in each of California’s 58 county-level juvenile justice systems. These systems, which will now take the place of DJJ by developing secure alternatives to state facilities, fall far short of the safe, restorative, and caring approach youth deserve. However, by closing the manifestly harmful DJJ institutions, advocates, families, lawmakers, and community members can now bring a unified focus to safeguarding youth at the local level.

Acknowledgements

This report was created in collaboration with the California Alliance for Youth and Community Justice (CAYCJ). Thank you to the many young people and family members who shared their experiences with us and with our partners. Special thanks to CAYCJ Director Abraham Medina and Deputy Director Israel Villa for their unfaltering commitment to keeping youth safe.

References

- American Civil Liberties Union Foundation (ACLU). (2019). Toxic Treatment: The Abuse of Tear Gas Weapons in California Juvenile Detention. At: https://www.aclusocal.org/site….

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology (AACAP). (2017). Solitary Confinement of Juvenile Offenders. At: https://www.aacap. org/aacap/policy_statements/2012/solitary_confinement_of_juvenile_offenders.aspx.

- Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC). (2023). 2022 Juvenile Titles 15 and 24 Regulations Revision. At: https://www.bscc.ca.gov/juveni….

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) (2010). Heman Stark youth facility closes after 50 years. February 22, 2010. At: https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/inside….

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). (2021). Pandemic Response at DJJ. At: https://web.archive.org/web/20….

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). (2022). Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) Transition Plan. At: http://www.cjcj.org/uploads/cj….

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). (2023). Guidelines for Visitors to Division of Juvenile Justice Facilities. At: https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/juveni….

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). (2023a). COMPSTAT Operational Performance Measure. Available upon request

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). (2018). DJJ Universal Glossary Definition. Available upon request.

- California Department of Education (CDE). (2023). California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress. English Language Arts/Literacy and Mathematics. 2021 – 22 School Year. California Education Authority (CEA) Hea. At: https://caaspp-elpac.ets.org/c….

- California Department of Finance (DOF). (2022). Memorandum of Understanding Addenda — Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Division of Juvenile Justice Retention Pay Differential. At: https://calmatters.org/wp-cont….

- California Department of Finance (DOF). (2022a). California Budget 2022 – 23 — Enacted. Corrections and Rehabilitation. At: https://ebudget.ca.gov/2022 – 23….

- California Department of Public Health (CDPH). (2022). Office of Communications. Fentanyl & Overdose Prevention. At: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Progra….

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Violence Prevention. Fast Facts: Preventing Sexual Assault. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. At: https://www.cdc.gov/violencepr….

- Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ). (2019). Unmet Promises: Continued Violence and Neglect in California’s Division of Juvenile Justice. At: http://www.cjcj.org/news/12466.

- Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ). (2020). A Blueprint for Reform: Moving Beyond California’s Failed Youth Correctional System. At: http://www.cjcj.org/news/12842.

- Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ). (2020a). California’s Division of Juvenile Justice Fails to Protect Youth Amid COVID-19. At: http://www.cjcj.org/news/13019.

- Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ). (2021). On the Brink: Conditions in California’s Division of Juvenile Justice Remain Bleak as Closure Nears. At: http://www.cjcj.org/news/13201.

- Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ). (2023). Division of Juvenile Justice Data. At: http://www.cjcj.org/Policy-ana….

- The Children’s Advocacy Institute (CAI). (2022). The Evolution of Juvenile Justice and Probation Practices in California: A history and review of juvenile justice as administered by county probation departments in California (1994−2019). At: https://caprinstitute.org/wp‑c….

- Dominguez, K. D. (2023). How Dangerous is Pepper Spray? National Capital Poison Center. At: https://www.poison.org/article….

- Hancock, K. (2017). Facility Operations and Juvenile Recidivism. OJJDP Journal of Juvenile Justice, 6(1): 1 – 14. At: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/2….

- Interviews (2022). CJCJ staff spoke with youth, family members, and staff from community-based organizations to inform the findings in this report.

- Los Angeles County, Board of Supervisors, (2023). Saving Lives by Making NARCAN Readily Accessible in the County’s Juvenile Hall Camps. Solis, Mitchell, Horvath, Barger & Hahn. At: https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSI….

- Lyons, B. (2023). State’s juvenile prison workers score $50,000 bonuses. CalMatters. At: https://calmatters.org/justice….

- Macallair, D. (2015). After the Doors Were Locked: A History of Youth Corrections in California and the Origins of Twenty-First-Century Reform. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Office of Inspector General (OIG). (2021). Discipline Monitoring. Case Summaries. Case No. 21 – 0039030-CM.

- Reeves, D. (2020). Gladiator School: Stories from Inside YTS. Vantage. At: https://gladiatorschool.medium….

- Juvenile justice realignment: Office of Youth and Community Restoration Senate (SB-823) Cal. Senate Bill No. 823. (2019−2020), Chapter 337 (Cal. Stat. 2020).

- State of California (CA). (2020). Governor Newsom Signs Critical Criminal Justice, Juvenile Justice and Policing Reform Package, Including Legislation Banning the Carotid Restraint. September 30, 2020.

- Thompson, D. (2018). Calif. weighs limits to pepper spray in juvenile jails. Associated Press, February 8, 2019. At: https://www.corrections1.com/j….

- Walker, T. (2022). “Gate Money” Bill Would Significantly Increase Assistance For Californians Returning Home From Prison. Witness LA. At: https://witnessla.com/gate-mon….

Please note: Jurisdictions submit their data to the official statewide or national databases maintained by appointed governmental bodies. While every effort is made to review data for accuracy and to correct information upon revision, CJCJ cannot be responsible for data reporting errors made at the county, state, or national level.

Contact: For more information about this topic or to schedule an interview, please contact CJCJ Communications at (415) 621‑5661 x. 103 or cjcjmedia@cjcj.org.

- 1 See Reeves, 2020. ↩

- 2 March 2020-April 2021 DJJ facilities halted visitation due to COVID-19 (CDCR, 2021). ↩

- 3 Suicide prevention terms as defined by the Division of Juvenile Justice. See DJJ Universal Glossary Definition (CDCR, 2018).Suicide Intervention: Suicide risk reduction status in which constant 1:1 observation is initiated by any Division of Juvenile Justice employee for youth who have been identified as having a risk of suicide.Suicide Precaution (SP): Suicide risk reduction status in which 1:1 observation is initiated and mental health intervention provided for youth who are at serious risk of engaging in self-injurious behavior.Suicide Watch (SW): Suicide risk reduction status in which constant 1:1 observation is initiated and mental health intervention provided for youth who have been determined by a mental health clinician to be in immediate and grave danger of committing suicide. ↩

- 4 Average excludes Pine Grove, which had no reported incidents in any category for December 2021- October 2023. ↩

- 5 Use of force terms as defined by the Division of Juvenile Justice. See DJJ Universal Glossary Definition (CDCR, 2018).Immediate Force: Refers to the use of reasonable force and due to time constraints, does not require authorization of a higher official when the behavior of a youth constitutes an imminent threat to the safety of any person or the security of the facility.Physical Force: Refers to a Correctional Peace Officer's use of department trained physical strengths and hold techniques to subdue an attacker, overcome resistance, effect custody, or effect custody. This also applies to a Division of Juvenile Justice employees [sic] ability to apply escape techniques to obtain distance from an attacking [sic] youth.Chemical Force: Refers to the use of division approved chemical agent(s).Less Lethal: Refers to the use of approved weapons that fire less than lethal projectiles that are used in serious incidents to include group disturbances. Mechanical Force: Refers to the use of division-approved mechanical restraint equipment. ↩

- 6 California Regulations 15 & 24 set the minimum standards for county-run juvenile justice facilities in California (BSCC, 2023). ↩

- 7 The true percentage may be higher due to some youth both holding jobs and taking classes. ↩