For more than a century, America’s juvenile justice system has reflected a deep and enduring tension between care and control. Beneath the language of “rehabilitation,” generations of young people — particularly from marginalized communities — have endured institutional neglect, violence, and systemic abuse. From reform schools to youth prisons, the promise of care has too often concealed systems of coercion and punishment. The Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ) was founded to confront this legacy. Through research, advocacy, and direct services, CJCJ works to expose institutional abuse, dismantle punitive structures, and promote community-based alternatives rooted in dignity, healing, and justice.

A Legacy of Institutional Abuse

From Punishment to “Reform”: The Birth of Youth Institutions

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, children accused of wrongdoing were routinely confined with adults in local jails and penitentiaries. Boys and girls were often detained for non-criminal behaviors such as poverty, “immorality” or vagrancy. Since there was no separate justice system for youth, they were crowded into filthy, violent facilities with adult offenders and people with mental illness.

Reformers such as Thomas Eddy and John Griscom sought to create more “humane” alternatives, leading to the establishment of the New York House of Refuge in 1825 — the nation’s first institution for “wayward” youth. Yet this model quickly reproduced the cruelty it claimed to replace. Children were subjected to physical abuse, solitary confinement, and forced labor. Poor and immigrant youth bore the brunt of the system’s harshest discipline. By the mid-19th century, dozens of similar facilities operated nationwide, embedding institutional control and abuse into the foundation of American juvenile justice.

Reform, Training, and Industrial Schools

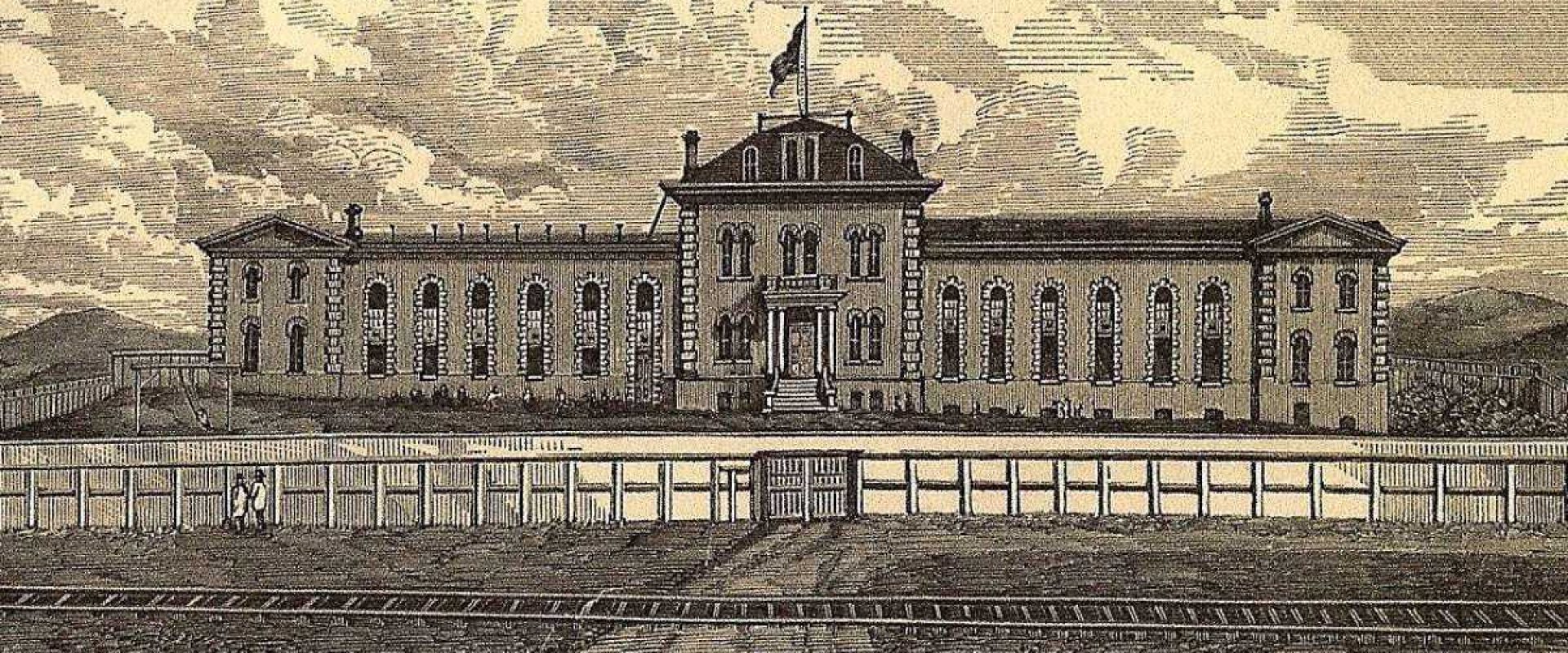

As public education expanded, reformers turned to “training” and “industrial” schools as solutions for delinquency. These institutions claimed to teach discipline and morality through work, yet conditions often mirrored prisons. Whippings, isolation, and hard labor were common. In California, the San Francisco Industrial School — founded in 1859 — became a notorious example of institutional cruelty. Reports of physical violence,

corruption, and neglect prompted public outrage and its closure in 1891. Yet across the nation, similar schools persisted. Behind the rhetoric of moral improvement lay a system of forced conformity and systemic abuse — especially targeting poor, immigrant, and later, Black and Indigenous youth.

The Rise of the Juvenile Court

The creation of the first juvenile court in Cook County, Illinois, in 1899 marked a pivotal shift. Advocates embraced the idea of parens patriae (“the state as parent”), promising individualized care over punishment. Yet this new system often perpetuated the same inequities and abuses under a veneer of benevolence. Judges wielded unchecked discretion, enabling arbitrary and discriminatory confinement. Youth of color, those from poor families, and children deemed “incorrigible” or “wayward” were disproportionately institutionalized. Investigations throughout the 20th century revealed widespread physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in state-run facilities — abuse that was routinely ignored or concealed.

Reform, Retrenchment, and Renewal

By the mid-20th century, revelations of abuse within reform and training schools eroded public trust. Landmark Supreme Court decisions extended due process protections to youth, yet institutional maltreatment persisted. The 1980s and 1990s ushered in a new wave of punitive policy. “Tough-on-crime” legislation expanded incarceration and blurred the line between juvenile and adult punishment. Overcrowding, racial disparities, and systemic neglect reached crisis levels, echoing the brutal conditions of 19th-century institutions. CJCJ emerged during this period of retrenchment, exposing institutional abuse in California’s youth prisons and advocating for their closure. Through litigation, research, and policy reform, CJCJ challenged the assumption that confinement equaled care — helping to catalyze a national rethinking of youth justice.

Toward a Just Future

Since the late 1990s, many states have shuttered abusive youth prisons and invested in community-based alternatives proven to reduce recidivism and promote healing. Yet the scars of institutional abuse remain visible in the lives of those harmed and in the systems that persist. CJCJ continues to lead efforts to end institutional confinement, confront the racial and structural violence embedded in juvenile justice, and replace punishment with opportunity. The path toward justice demands acknowledging the full history of abuse — so

that future generations of youth will never again suffer under institutions that claim to

“reform” while inflicting harm.

Obtain your copy of The San Francisco Industrial School and the Origins of Juvenile Justice in California: A Glance at the Great Reformation by CJCJ Executive Director Daniel Macallair.

- Bakal, Yitzak, and Howard Polsky. Reforming Corrections for Juvenile Offenders.

- Bush, William S. Who Gets a Childhood? Race and Juvenile Justice in Twentieth-Century Texas.

- Chávez-García, Miroslava. States of Delinquency: Race and Science in the Making of California’s Juvenile Justice System.

- Coates, Robert, Alden D. Miller, and Lloyd E. Ohlin. Diversity in a Youth Corrections System: Handling Delinquents in Massachusetts.

- Feld, Barry C. The Evolution of the Juvenile Court: Race, Politics, and the Criminalizing of Juvenile Justice.

- Lemert, Edwin. The Juvenile Court System: Social Structure and Process.

- Macallair, Daniel. After the Doors Were Locked: A History of Youth Corrections in California and the Origins of 21st Century Reform.

- Miller, Alden D., and Lloyd E. Ohlin. Delinquency and Community: Creating Opportunities and Controls.

- Miller, Jerome G. Last One Over the Wall: The Massachusetts Experiment in Closing Reform Schools.

- Schlossman, Steven L. Transforming Juvenile Justice: Reform Ideals and Institutional Realities, 1825 – 1920.

- Schur, Edwin M. Radical Nonintervention: Rethinking the Delinquency Problem.

- Society for the Prevention of Pauperism. Report on the Penitentiary System in the United States.

- Tanenhaus, David S. Juvenile Justice in the Making.

- Ward, Geoff K. The Black Child-Savers: Racial Democracy and Juvenile Justice.

- Woodson, Kenneth. Weeping the Playtime of Others.